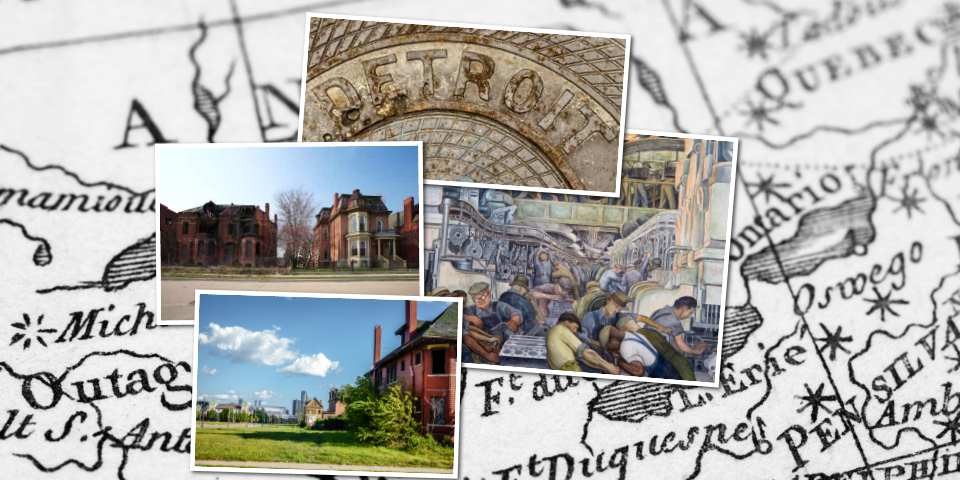

The system of dispossession in the United States, particularly for land and/or housing, is one of the most significant, historical methods of accumulation of wealth for whites and of disaccumulation for African-Americans and other people of color. Unfortunately, this phenomenon is perhaps best exemplified by the city of Detroit, Michigan, due to the devastatingly negative consequences of deindustrialization, white flight, urban decay, and -- most recently -- the Great Recession.  Even as revitalization narratives about the city (particularly Detroit’s downtown) in traction among public officials, investors, and the media, Detroit’s outer neighborhoods continue to be decimated by the greed of land speculators and policies written - in my view - by and for the economically privileged. After reviewing the history, I have come to the conclusion that - through seemingly unrelated methods such as municipal bankruptcy, tax foreclosure, emergency manager laws, urban renewal, eminent domain, land speculation, and property taxes - Detroit has methodized a sequence of plunder against its working class population, which predominantly consists of people of color (U.S. Census Bureau 2019), in order to attract capital that can feed revitalization narratives about the city.

Even as revitalization narratives about the city (particularly Detroit’s downtown) in traction among public officials, investors, and the media, Detroit’s outer neighborhoods continue to be decimated by the greed of land speculators and policies written - in my view - by and for the economically privileged. After reviewing the history, I have come to the conclusion that - through seemingly unrelated methods such as municipal bankruptcy, tax foreclosure, emergency manager laws, urban renewal, eminent domain, land speculation, and property taxes - Detroit has methodized a sequence of plunder against its working class population, which predominantly consists of people of color (U.S. Census Bureau 2019), in order to attract capital that can feed revitalization narratives about the city.

Although at the outset of this project I could not identify how these seemingly unrelated factors came together to produce a crisis, their interrelationship is painfully clear now. First, through policies such as redlining, African-Americans (as well as members of other marginalized racial groups) - the descendants of those once deemed property by European colonists - are ghettoized, limited in the property they can own and crammed into claustrophobic urban centers. Next, as the greed of the U.S. banking class, implicitly supported by a lack of government oversight (Labaton 2008), leads to the collapse of the world housing market in 2008, the city of Detroit fails to properly correlate property taxes with the new, lower value of the city’s residential properties (Vice News on HBO 2017) (Note: state and local government recently made attempts to protect homeowners caught in this predicament. See Meloni and Hutchinson 2020.) Then, after years of charging residents interest on the balance of their already-inflated property taxes, the county seizes their homes when they are inevitably delinquent on a third year’s payment (albeit with a one-year grace period to repay one’s debt to the city and regain property. See Loftsgordon 2020).

From there, local, state, and federal governments put forth policies that worsened the problems they themselves created. This was exemplified by Michigan Gov. Rick Snyder’s appointment of an emergency manager to control Detroit’s finances. This act, in combination with years of urban “renewal” projects, failed the city’s low-income residents. Some would say that the wealthy benefitted at the poor’s expense. Finally, once a foreclosed Detroit home is acquired by an investor, the working person who lived there all along is turned into a renter in his, hers, or their own home, facing either the indignity of being lorded over on land they should rightfully own or being displaced entirely (Gallagher 2017).

Owning a home is the quintessential symbol of social mobility in the United States. It imparts owners not only status but also potentially enhances their ability to build more wealth (Martin 2019). Such investments can also, in some measures, impart esteem and confidence that so many people – including working-class and working poor men and women who devote their lives to powering our country and economy – deserve. Throughout this project, I have tried to elucidate the systemic injustices and inequalities that lead to the displacement of low-income homeowners, not to show these residents and their communities as fundamentally broken or in need of saving, but to demonstrate the true desire for a better life and safe surroundings that persists in the face of incomprehensible discrimination. Moving forward, collectively - with advocates from inside the community and allies from outside of it - society must promote policies that recognize the innate dignity of all human beings and understand that such dignity necessitates safe and affordable housing for every man, woman, non-binary person, and child. Such policies include allowing for more hardship exemptions for property taxes (especially when the level of taxation is under dispute) retroactive property tax exemption, eliminating the notary requirement for property tax relief, reparations for those preyed upon by redlining, and the establishment of a community land trust that will help working Detroiters purchase a home cheaply. In short, society must fight for the realization of British sociologist T.H. Marshall’s vision: that all people deserve “[t]he right to a modicum of economic welfare and security [and] the right to share to the full in the social heritage…” of the place they call home.

READ THE THE FULL SERIES

The Sequence of Plunder: A Case Study of Housing Dispossession in Detroit, Part I

The Sequence of Plunder: A Case Study of Housing Dispossession in Detroit, Part II

The Sequence of Plunder: A Case Study of Housing Dispossession in Detroit, Part III

The Sequence of Plunder: A Case Study of Housing Dispossession in Detroit, Part IV

The Sequence of Plunder: A Case Study of Housing Dispossession in Detroit, Part V

WORKS CITED

Gallagher, John. “Foreclosure Crisis Makes Detroit a City of Renters, Not Homeowners.” USA Today, Gannett Satellite Information Network, 21 Mar. 2017, www.usatoday.com/story/money/nation-now/2017/03/20/foreclosure-crisis-ma....

Labaton, Stephen. “S.E.C. Concedes Oversight Flaws Fueled Collapse.” The New York Times, The New York Times, 26 Sept. 2008, www.nytimes.com/2008/09/27/business/27sec.html.

Loftsgordon, Amy. “Getting Your Home Back After a Property Tax Sale in Michigan.” Www.nolo.com, Nolo, 9 Jan. 2020, www.nolo.com/legal-encyclopedia/getting-your-home-back-after-property-tax-sale-michigan.html.

Martin, Erik. “Want to Build Wealth? Buy a Home.” Hsh.com, 23 Sept. 2019, www.hsh.com/first-time-homebuyer/build-wealth-buy-a-home.html.

Meloni, Rod, and Derick Hutchinson. “New Law Helps Detroit Residents Who Fall behind on Property Taxes.” WDIV, WDIV ClickOnDetroit, 2 Mar. 2020, www.clickondetroit.com/news/local/2020/03/02/new-law-helps-detroit-residents-who-fall-behind-on-property-taxes/.

“People Are Making Big Money Kicking Detroit Residents Out Of Their Homes.” Online video clip. YouTube. HBO. 7 Dec 2017. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=gHLaWw_PnQY. 27 Mar 2020.

“U.S. Census Bureau QuickFacts: Detroit City, Michigan.” Census Bureau QuickFacts, www.census.gov/quickfacts/detroitcitymichigan.

Troy Distelrath is an undergraduate IPPSR Policy Fellow pursuing an academic career in public policy.

Troy Distelrath is an undergraduate IPPSR Policy Fellow pursuing an academic career in public policy.