The most widely-cited and circulated indicator of economic health is the unemployment rate, touted in success stories as evidence of recovery. The decline from its peak of 15.2% in June 2009 down to 4.0% in June 2017 demonstrated a drastic improvement from the Great Recession. But considering the needs of the state and its economic make-up have changed since then and the declining size of the workforce has called into question the real driver of low unemployment rates, it is necessary to explore whether steadily low jobless rates should continue to be celebrated and highlighted or if attention should turn to alternate labor market indicators.

Workforce Size

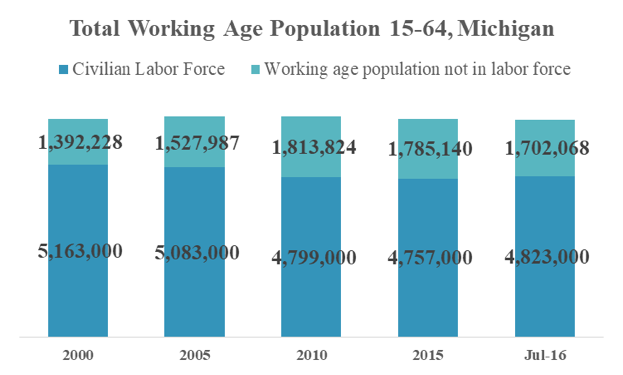

In spite of low jobless rates, Michigan's total workforce dropped by over 300,000 people since 2000. Based on the U.S. Census Bureau’s American Community Survey, Michigan’s population of working-age adults between 15 and 64 remained relatively steady over the same time period, making it unlikely that an aging population is to blame for dwindling workforce participation. The gap between the total population of working-age adults and the total civilian labor force offers a glimpse at how many individuals in Michigan within the typical working-age range are not participating in the labor market. Standing at around 1.7 million people in July 2016, this would include those not participating for reasons ranging from discouragement to disability to higher education, and more. Additionally, as some individuals within the labor force are over 64 years old, and because older age cohorts were one of the few groups to see an increase in labor force participation over this time period, the working-age population not in the labor force is likely understated.

In spite of low jobless rates, Michigan's total workforce dropped by over 300,000 people since 2000. Based on the U.S. Census Bureau’s American Community Survey, Michigan’s population of working-age adults between 15 and 64 remained relatively steady over the same time period, making it unlikely that an aging population is to blame for dwindling workforce participation. The gap between the total population of working-age adults and the total civilian labor force offers a glimpse at how many individuals in Michigan within the typical working-age range are not participating in the labor market. Standing at around 1.7 million people in July 2016, this would include those not participating for reasons ranging from discouragement to disability to higher education, and more. Additionally, as some individuals within the labor force are over 64 years old, and because older age cohorts were one of the few groups to see an increase in labor force participation over this time period, the working-age population not in the labor force is likely understated.

Job Industries

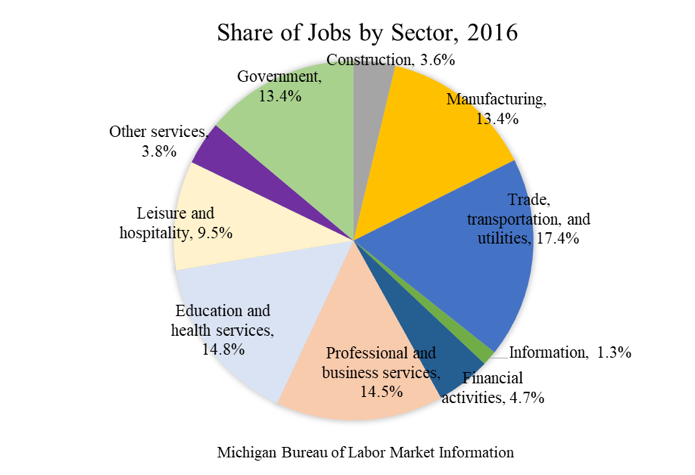

From the Michigan Bureau of Labor Market Information’s Current Employment Statistics, a breakdown of the industries that provide jobs in Michigan offers a look further than whether or not people have jobs, but what type of work they do. Despite Michigan’s longtime reputation as a manufacturing-heavy workforce, the manufacturing industry was only responsible for 13.4% of Michigan jobs last year, a sharp contrast from its status as the No. 1 job-providing industry in 2000 at 18.1%. The largest industry for jobs in 2016 was the trade, transportation, and utilities industry with 17.4%, followed by education

From the Michigan Bureau of Labor Market Information’s Current Employment Statistics, a breakdown of the industries that provide jobs in Michigan offers a look further than whether or not people have jobs, but what type of work they do. Despite Michigan’s longtime reputation as a manufacturing-heavy workforce, the manufacturing industry was only responsible for 13.4% of Michigan jobs last year, a sharp contrast from its status as the No. 1 job-providing industry in 2000 at 18.1%. The largest industry for jobs in 2016 was the trade, transportation, and utilities industry with 17.4%, followed by education  and health services and professional and business services at 14.8% and 14.5%, respectively.

and health services and professional and business services at 14.8% and 14.5%, respectively.

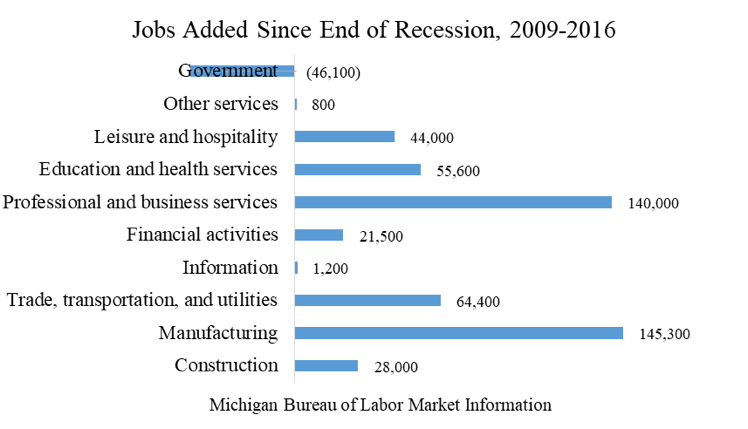

Since 2009, more than 400,000 jobs have been added back into the economy after substantial losses were experienced in the recession. Though manufacturing may no longer be the largest job-providing industry in the state, it surpassed every other industry (albeit professional and business services only slightly) in terms of jobs created since the end of the recession.

Wages

While mean (or average) wages are typically higher than median, an uneven wage distribution due to extremely high wages at the top can skew estimates and suggest higher incomes than are truly representative in the population; median wages provide a look at what ‘most’ individuals earn, showing the level where half of all workers earn below. Annually, median income grew from $33,740 in 2009 to $36,030 in 2016 (not adjusted for inflation), below the national annual median of $37,040.

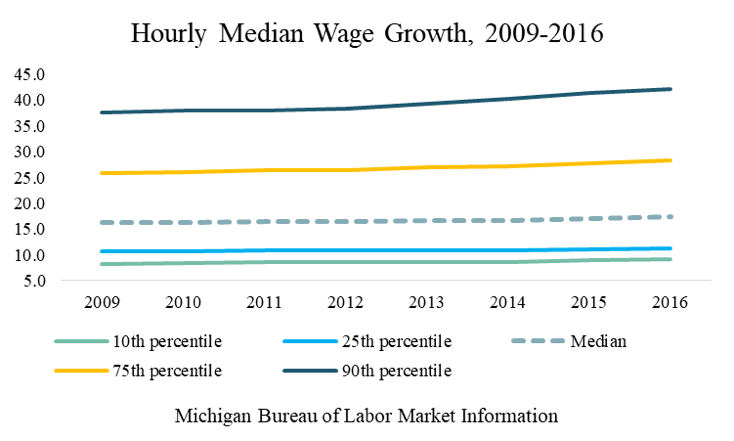

Hourly wages have seen relatively stagnant growth between 2009 and 2016. The median hourly wage, representing the wages in the middle of all workers, grew from $16.22 in 2009 to $17.32 in 2016, compared to the national median hourly wage of $17.81. Hourly wages for the lowest 10th percentile of workers grew from $8.19 in 2009 to $9.16 in 2016, and for the workers earning in the highest 90th percentile, hourly wages increased from $37.62 in 2009 to $42.10 in 2016.

The growth of jobs in the professional and business services and manufacturing sectors indicate a promising influx of quality jobs, but stagnating wage growth suggests not all are progressing from such employment. And a decreasing labor force can be indicative of problems beneath the surface of the workforce and even beyond it; researchers have developed a plethora of hypotheses on reasons for declining labor force participation, including opioid addiction, high incarceration rates, increased persons with disabilities and more.

Now that the unemployment rate is no longer a cause for concern, taking a deeper look at weaker aspects of Michigan's labor market would be a prudent next step in helping the state's economy continue to truly strengthen and grow. Knowing that those in Michigan who desire to work are much more likely to find employment than they were a decade ago means the state is now well-positioned to turn its focus to the quality of available jobs, rather than simply ensuring adequate quantity.

Abbey Frazier is a graduate policy fellow at the Institute for Public Policy and Social Research.