The risks of childhood lead exposure and poisoning were inadvertently brought into the spotlight through the Flint water crisis. But the issue in Michigan extends far beyond that city's limits.

The risks of childhood lead exposure and poisoning were inadvertently brought into the spotlight through the Flint water crisis. But the issue in Michigan extends far beyond that city's limits.

Last November, the Michigan Department of Health and Human Services released provisional 2016 data on childhood lead testing showing that the rate of elevated lead levels in Michigan children under six years old increased for the first time since 1998. Despite declines in lead exposure for children in Flint, the slight uptick from 3.4 to 3.6 percent was mostly driven by increases in other Michigan cities like Grand Rapids and Detroit.

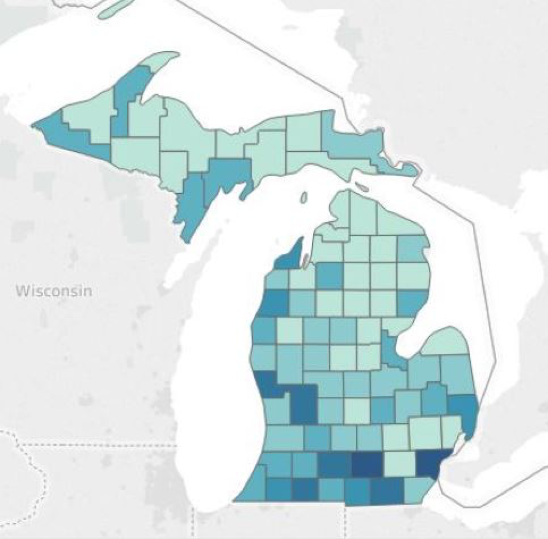

High rates of lead poisoning in counties across the southern and western regions of the state are shown in the above map. One particular zip code in Grand Rapids saw more children poisoned by lead in 2016 than during the entirety of the Flint Water Crisis, and Detroit saw a 28 percent spike in the number of children poisoned by lead.

Instead of originating from a polluted water supply like in Flint, lead poisoning in children across Michigan is mostly caused by lead-based paint and dust in older homes, a particular problem for children in low-income neighborhoods.

The map above displays the percent of Michigan children younger than six years old with elevated blood lead levels, greater than 5 micrograms per deciliter by county in 2016.

Lead exposure in young children is strongly associated with developmental delays, problems with brain functioning, aggressive or violent behavior later in life and adverse educational outcomes. Those who have experienced lead poisoning as children have been found to be seven times more likely to drop out from high school.

Some of the rise in elevated lead levels can be attributed to more aggressive screenings in the wake of the Flint water crisis, though the rate of increase is greater than that of increased testing. Even with increased screenings, only around 20 percent of Michigan children under six years old were screened for elevated levels of lead in 2016, suggesting that the full scale of the problem may still be unknown.

In addition to Grand Rapids and Detroit, other cities with high rates of elevated lead levels include Kalamazoo, Battle Creek, Jackson, and Muskegon. While 1.8 percent of children in Flint’s Genesee County were found to have high levels of lead in their blood, that compares to 7.6 percent in Jackson County, 6.7 percent in Kent County, and 8.8 percent in Detroit.

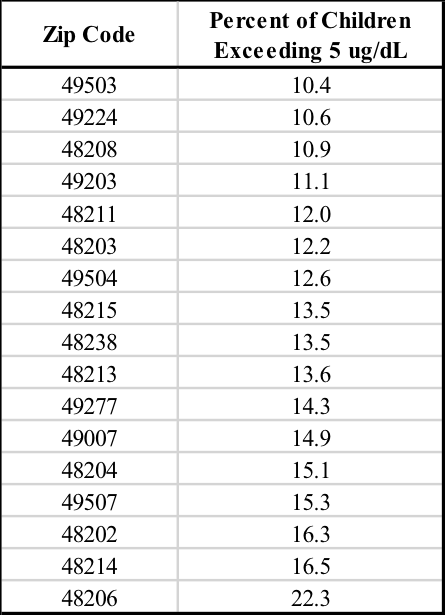

Areas in Detroit were found to have some of the highest rates of child lead poisoning in the state. Of the 17 zip codes in Michigan where more than 10 percent of children tested positive for lead poisoning, 10 were in Detroit. In the Detroit zip code 48206, more than 22 percent of children tested were found to have elevated lead levels in their blood. The chart below represents the Michigan ZIP codes with the worst lead poisoning levels.

Due to lead residue trapped in soil, there has also been some evidence of a link between housing demolitions in Detroit and lead poisoning in children living nearby. To address the issue the City of Detroit Health Department created a task force charged with developing recommendations to reduce exposure, including improving transparency and communication with residents, expanding the notifying area, and providing vouchers to families with young children to allow for temporary relocation.

Kent County created their own task force to address high lead levels in Grand Rapids children, recently releasing a list of recommendations aimed at reducing childhood exposure. The Grand Rapids zip code 49507 was among the highest in the state with 15.3 percent of children testing positive for elevated levels of lead in their blood. The Kent County task force’s recommendations aim to increase awareness and information through public education, better evaluate the problem using policy initiatives, reduce risk by identifying and eliminating causes, and expand testing and treatment efforts in health care. Other local efforts include Healthy Homes Initiatives like the Healthy Homes Coalition of West Michigan, ClearCorps/Detroit, and Lead Safe Lansing.

In 2016, the Governor created by executive order the Child Lead Poisoning Elimination Board to address childhood lead exposure in Michigan. The commission released more than 100 recommendations in late 2016 covering five key areas: testing, case management and monitoring, environmental investigations, remediation and abatement, and dashboards and reporting. The report called for universal testing of children between 9 and 12 months and again around 2 years, and a uniform, statewide database to track and monitor efforts across the state. The recommendations were never taken up by the legislature.

State officials have also received permission to use federal Children’s Health Insurance Program (CHIP) funding to expand lead abatement efforts in Flint and across the state, which will amount to $24 million per year over the next five years. The focus of these efforts will include the removal of lead based paint, home fixtures containing lead such as water service lines, and lead-contaminated soil in Flint and other high-risk communities across the state.

Though child lead exposure in Flint was a unique case resulting from a man-made environmental disaster, the tragedy brought to light existing problems with childhood lead poisoning in areas beyond Flint. Before the Flint Water Crisis occurred, Michigan was ranked the fifth worst state in the nation by the CDC for childhood lead poisoning, and it has been estimated by the Ecology Center that in 2014 child lead poisoning cost the state at least $270 million per year in increased health, criminal justice, special education costs and lost labor force productivity. Aggressive and sustained efforts to combat child lead exposure will be a critical piece to ensuring that all Michigan children, particularly those in high-risk neighborhoods and communities, have a chance to succeed without the threat to their safety of the irreversible and long-term damage caused by lead poisoning.

Abbey Frazier is a graduate policy fellow at the Institute for Public Policy and Social Research.