THE CASE FOR STATE-LEVEL CHILD TAX CREDITS

AN IPPSR REPORT BY MADELEINE MARCH-MEENAGH

COMPELLING EVIDENCE

Research shows that kids are in crisis. A 2017 UNICEF report on the status of children in developed countries identified nine “child-relevant goals” by which to judge the world’s richest countries. The United States scored below average on six out of the nine indicators. In regard to child poverty, the U.S. was significantly below average with a rank of 33 from among 37. [1] Drawing from recent data from the U.S. Census Bureau, the U.S. Children's Defense Fund identified evidence of a “continued child poverty crisis” nationwide. Among all age groups, children are the poorest, with the youngest children being the worst off.[2] Across the country, one out of every six children live in poverty and children account for one third of all individuals living in poverty.[3] The statistics are more devastating for children of color who are 2.5 times more likely to be poor than white children.[4] One in four American children of color are poor and comprise nearly 75% of all children in poverty.[5]

The effects of childhood poverty are longitudinal and multi-dimensional. Though usually framed in acute terms such as missing a meal or not having a winter coat, research points to the considerable cumulative effects of childhood poverty that can last into adulthood. Poverty is linked with increased neonatal and post neonatal mortality rates.[6] Lower socioeconomic status leads to lower educational and developmental outcomes from infancy onward.[7] Poverty can “trigger toxic stress” which can “negatively impact a child’s brain functioning for life.” Through experiencing increased levels of stress, not having access to enough nutritious foods[8], and being more likely to live in polluted environments, children who live in poverty experience diminished health outcomes.[9] Poverty decreases a child’s school-readiness and their likelihood of graduating from high school.[10] It is no surprise that the agglomeration of these and other factors reinforce the intergenerational cycle of poverty as their compounded effects can have “lasting consequences into adulthood.”[11]

The good news is that the American public is ready to end child poverty — and believes it is the government’s responsibility to do so. In an extremely polarized political climate, the plight of children is common ground. In fact, when prompted to consider how they would “change the world if they could make just one change,” most Americans agree that ending childhood poverty, hunger, and homelessness is the way forward.[12] A majority of Americans believe the “only way” to address child poverty is by “provid[ing] more assistance to their parents” and nearly 90% support tax breaks for low-income parents. Only a third of parents contend the “government is doing enough to end child poverty.”[13]

THE CTC AS A TOOL TO COMBAT CHILD POVERTY

Child poverty isn’t new, as evidenced by its earlier characterization as a “continued” crisis. For more than 30 years, leaders across the world have prioritized the plight of poor children. However, despite similar goals, the impact of initiatives to address child poverty have been “surprisingly different” with the U.S. outcomes significantly trailing countries such as the U.K. and Canada. In a time shaped by public animosity toward government spending, the U.S. has been able to increase spending on poor families through the expansion of tax expenditures.[14] The political advantage of tax expenditures over traditional social spending lies in how they’re classified. Because tax credits are typically labeled as “revenue not collected,” the credits don’t show up in spending budgets, allowing politicians to circumvent their price tag publicly.[15] This trend in the U.S. is best exemplified through the continued expansion of the federal earned income tax credit (EITC) and child tax credit (CTC).

In each of the four past presidential administrations, the federal CTC has been expanded – and with relative ease due in part to its obfuscated cost and name. The politics surrounding an issue are often simplified if the policy’s purpose is framed as being for children. As stated earlier, the public supports such measures en masse.

The current federal CTC is a partially refundable tax credit available to qualifying parents who have children under the age of 17. Taxpayers can claim a credit of up to $2,000 per child. The credit is reduced for families with an adjusted gross income of more than $200,000 for single parents and $400,000 for married couples. If the credit exceeds taxes owed, taxpayers are eligible to receive at maximum $1,400 as a refund. This refund is referred to as the additional child tax credit (ACTC). However, no credit is available to families earning $2,500 or less per year.[16]

Because the CTC is relatively new compared to its more established working-family tax credit companion, the earned-income tax credit (EITC), less research has been conducted on the CTC specifically. However, because the CTC “shares key design features “with the EITC (i.e., is available only to working families and phases in as earnings increase), experts posit that they likely yield similar benefits. Namely, a robust body of research shows that the recipients of working-family tax credits and their children reap intergenerational work, income, educational, and health benefits.[17] Furthermore, these benefits directly combat systemic inequalities facing people of color and those bearing a low socio-economic status.

Research shows that income supplements, like the CTC, improve children’s outcomes in three fundamental ways: economically, psychologically, and epidemiologically.[18] With increased income, parents are able to “acquire more resources needed for healthy development, such as nutritious meals, enriched home environments, and high-quality child care, and allows them to live in neighborhoods free of crime and air and noise pollution.”[19] Augmented incomes also ameliorate familial stress levels. When parents are less stressed, anxious, and/or depressed, they are able to parent in less harsh and more supportive styles; meanwhile, children are not internalizing the poverty-induced stress and instability fostered by their environments.[20]

Canada’s Child Benefit, essentially that country’s version of the U.S. CTC, has significant positive relationships with child test scores, maternal health, and, for both parent and child, mental and physical health.[21] In the United States, children whose parents benefit from the federal CTC “do better in school, are likelier to attend college, are healthier, are likelier to avoid the early onset of disabilities and other illnesses associated with child poverty, and work and earn more as adults.”[22] The CTC has even been linked to increased Social Security retirement benefits thereby reducing the likelihood of its beneficiaries to need government assistance in old age.[23] In sum, the CTC has a significant effect on the poverty experienced by families nationwide.

A STATE-LEVEL CTC AS A SUPPLEMENT AND SOLUTION

The federal child tax credit has been accused of being “poorly targeted -- “excluding the families most in need”[24] – because it is non-refundable and families who make less than $2,500 are ineligible. These restrictions leave rural families, larger families, families of color, military families, and families with young children disproportionately uncovered.[25] In response, multiple leading non-profit organizations have called on states to bridge the gap for their families in need. Earlier this year, the National Academies of Sciences, a non-partisan, non-profit organization comprised of the nation’s leading researchers, published A Roadmap to Reducing Child Poverty, a consensus study report prepared for the U.S. Congress which identified expanding child tax credits as the optimal approach to halve child-poverty over the next decade. Likewise, the Institute on Taxation and Economic Policy teamed up with the Center on Poverty & Social Policy at Columbia University to create a 50 state analysis making the case for extending state-level child tax credits to those “left out.” The Center for American Progress released a report urging states to “[h]arness” state-level child tax credits to “drastically reduce child poverty.”

The reports urging the adoption of more state-level CTCs all call for refundable child tax credits so that families most in need are able to benefit, yet half of the state-level CTCs are non-refundable. For those less familiar with refundable versus non-refundable tax credits, the implications may not be immediately clear. When a tax credit is non-refundable, it operates to reduce the amount of tax money the taxpayer owes. If the credit is larger than the amount owed, the taxpayer will not be able to claim the entire credit. Alternatively, a taxpayer can claim a refundable credit in its entirety regardless of the amount of taxes they owe. If the credit claimed is larger than the tax burden, the excess will be included in the taxpayer’s refund. When a tax credit is non-refundable, it operates to reduce the amount of taxes the taxpayer owes. If the credit is larger than the amount owed, the taxpayer will not be able to claim the entire credit. Alternatively, a taxpayer can claim a refundable credit in its entirety regardless of the amount of taxes they owe. If the credit claimed is larger than the tax burden, the excess will be included in the taxpayer’s refund.

By making the CTC fully refundable, instead of partially refundable as is the federal CTC, states would allow all poor children to benefit.[26]Four states have recently sought to supplement the federal CTC with their own state version. By taking different approaches, they provide compelling case studies to consider for others looking to follow their lead. Two of them have implemented a refundable approach; the other two a non-refundable credit. Because the state-level CTCs are relatively recent implementations, research on their impact has not yet been conducted.

CASE STUDY: STATE-LEVEL CHILD TAX CREDITS

Use and cost listed per year

TAX CREDIT STRUCTURE: NONREFUNDABLE CTC POLICIES

IDAHO

IDAHO

Eligibility: Based on the federal CTC

Rate: $205 per child

Use: ~100,000[27] Idahoans

Cost: ~$69 million[28]

Effect: Idaho’s CTC expands the benefits of the federal CTC. However, because Idaho’s CTC is nonrefundable, many low-income families don’t benefit. As a result, tax relief was “mostly concentrated among higher-income filers, specifically those with smaller families.”[29]

OKLAHOMA[30]

Eligibility: All Oklahoma taxpayers who qualify for the federal credit are automatically eligible as long as their incomes are less than $100,000.

Eligibility: All Oklahoma taxpayers who qualify for the federal credit are automatically eligible as long as their incomes are less than $100,000.

Rate: Eligible families may claim either 5% of the federal CTC or 20% of the federal CDCTC, whichever is greater.

Use: ~365,000 Oklahomans

Costs: ~$23.9 million

Effect: Oklahoma’s CTC also expands on the benefits of the federal CTC, but limits the benefits only to those making below $100,000. Because the CTC is non-refundable, many low-income Oklahomans don’t benefit. However, unlike Idaho, tax relief is not concentrated among high-income filers because of the aforementioned benefit cutoff.

TAX CREDIT STRUCTURE: REFUNDABLE CTC POLICIES

CALIFORNIA[31]

CALIFORNIA[31]

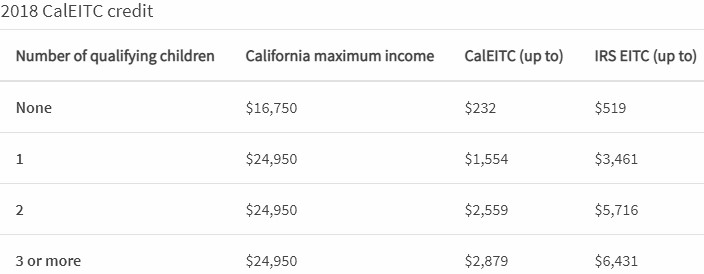

Eligibility: Available to families making less than $30,000 with a child under the age of 6 based on the CalEITC sliding scale below.

Rate: Sliding scale up to $1000 per family

Use: ~400,000 Californian families

Cost: ~$360 million

|

Effect: By design, the California CTC only benefits young children (i.e., those under the age of six) unlike the federal CTC. However, it benefits families with very low-incomes (i.e., those making less than $9,200/ year) more than the federal CTC. It does this by providing a fully refundable credit to families who make as little as $1 annually.[32]

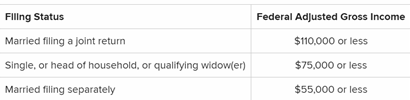

NEW YORK[33

Eligibility: Either based on federal CTC or adjusted gross income is:

Rate: $100 per qualifying child* or 33 percent of the taxpayer’s federal credit, whichever is greater.

*A qualifying child must be at least four but less than 17 years old on December 31st of the tax year and must qualify for the federal child tax credit.

Use: ~1.44 million

Cost: ~$633 million

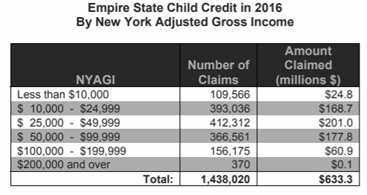

Broken down by tax bracket courtesy of the New York Department of Taxation and Finance:

Effect: Unlike California’s CTC, children under the age of four do not qualify for the Empire State Child Credit. However, like California, it does boast a fully refundable credit which allows it to extend benefit to families with very low incomes as shown in the table above.

WHY MICHIGAN SHOULD CONSIDER A STATE CTC

Because Michigan is home to many of the groups most likely to have been excluded by the federal CTC (e.g., rural families and families of color) and struggles with many of the issues ameliorated by the CTC (e.g., childhood educational and health outcomes), Michigan would benefit significantly from implementing a state child tax credit. State CTCs “not only enable state policymakers to invest in the next generation and future workforce, but they can also be used to counteract the inequities and shortcomings of [the] federal [CTC].”[34]

THE STATE OF THE STATE

Michiganders experience child well-being outcomes below the national average[35], and their experiences heavily depend on their race.[36] According to the 2019 Kids Count Michigan Data Book, Michigan children struggle across multiple dimensions that could be addressed by a state-level CTC, namely vis-à-vis economic security, health, and education. Nearly 1 in 5 kids live below the federal poverty line (FPL) in Michigan.[37] Parents earning full-time wages at a minimum wage job spend, on average, more than 35% of their income on child care alone.[38]

Families of color are more likely to have lower incomes than white families statewide. Black children are twice as likely to be in families with less than 200% of FPL than white children.[39] These material differences have translated into significant racial health and educational outcomes for Michigan’s children. Black children are twice as likely to die before they turn 1 than white children, and Latinx infant mortalities are on the rise.[40] Meanwhile, more than half of Michigan third graders read below proficient levels. Nearly 70% are not proficient in math. More than 50% of the state’s 3- and 4-year-olds are not enrolled in preschool. On the other end of the school system, 65.4% of Michigan’s high schoolers are not college ready and 1 in 5 of them will subsequently not graduate from high school on time.[41]

If nothing is done, children in poverty, and children of color more specifically, will be “disproportionately impacted.”[42] Fortunately, Michigan has options. As a guideline, the Center for American Progress suggests state CTCs are most effective when they:

- Target all low-and middle- income children

- Deliver an extra boost to the youngest children

- Include disabled adult children, and

- Strengthen existing federal credit. [43]

To do this, Michigan should consider a fully refundable CTC. If it isn’t feasible to provide a fully refundable tax credit for everyone who benefits from the federal CTC, ensuring the expanded refundability for families with children under 6 would be an effective step forward. While there are a broad range of policy options (e.g., non-refundable vs. refundable, targeted eligibility, etc.) at Michigan’s disposal, this report outlines six options. The first three are based on established state models, the next two are targeted for families with young children, and the remaining are as put forth by The Institute on Taxation and Economic Policy.

POLICY ALTERNATIVES & ESTIMATED IMPACTS

OPTIONS BASED ON ESTABLISHED STATE MODELS

OPTION 1: NONREFUNDABLE CTC BASED ON OKLAHOMAN MODEL

Eligibility: All taxpayers who qualify for the federal credit are automatically eligible as long as their household incomes are less than $100,000.

Rate: Eligible families may claim 5% of the federal CTC

Est. Impact: 890,774 households

Est. Cost: $144,744,032

Because this option is nonrefundable, it is less costly than a refundable CTC; however, literature suggests that nonrefundable CTCs are significantly less effective at lifting families out of poverty than their refundable counterparts. By basing the state CTC eligibility on the federal credit (i.e., $2,500 income phase-in), there is a diminished effect on families with the lowest incomes. The $100,000 income upper limit keeps the price tag down by targeting the state credit’s impact to those who have more need and to whom the tax relief will have the most impact.

OPTION 2: REFUNDABLE CTC BASED ON NEW YORK MODEL

Eligibility: All taxpayers who qualify for the federal credit are automatically eligible as long as their household incomes are less than $100,000 with no $2,500 phase-in

Rate: $80 per child or 12 percent of the taxpayer’s federal credit, whichever is greater.

Est. Impact: 942,990 households

Est. Cost: $368,737,678

The second option costs more because it is refundable, the benefit is higher, and there is no phase-in requirement; however, it likewise boasts a larger impact than does the first. Not only are more people eligible for this option, the impact on each family is likely to increase in magnitude because the credit is refundable. Between making the credit refundable and eliminating the income minimum, this option is able to better serve families in poverty and deep poverty. The rates and income limits for this option were adjusted to account for cost-of-living differences between New York and Michigan.

OPTION 3: CONVERTING PERSONAL EXEMPTIONS TO REFUNDABLE CTCS

Eligibility: All taxpayers with children under 18

Rate: $200/child

Est. Impact: 168,185 households

Est. Cost: $62,895,584 to supplement the cost already associated with dependent exemptions

A state CTC can mirror the federal CTC making implementation rather simple (see Idaho), but can also expand its impact by making it fully refundable. In this way, Michigan would be able to assist low-income families in a way that the federal CTC cannot. For further impact, the state could consider lowering the amount a family has to earn to qualify for the credit (see California). To mitigate revenue loss, Michigan could lower the income level at which the credit phases out (see Oklahoma and California). To calculate the credit value needed to replace a personal exemption, the Tax Policy Center suggests “multiplying the amount of income exempted from tax by the tax rate at which that income would be taxed if it were not exempt.”[44] That means in Michigan, the credit value necessary to replace the personal exemption is ~$200 in FY2020 ($4,750 x 4.25%).

EVIDENCE-BASED TARGETED OPTIONS

Research has long reinforced how critical early childhood experience is to an individual’s long-term development. Children are “especially likely” to suffer the negative, long term effects of poverty if they experience poverty when they are “very young”.[45] Moreover, parents with young children often have lower incomes than other families.[46] Yet, restrictions on the current federal CTC leave families with young children disproportionately uncovered.[47] Both options below provide an “extra boost” to families with young children which aligns with best practice.[48] Previous research evidences the positive relationship between income boosts during early childhood with an individual’s long-term lifetime outcomes.[49] In fact, because of the significant impact early childhood maintains, dollars targeted to families with young children are thought to be more efficiently used than more universal models. As such, these options have smaller price tags but just as big of an impact.

Option Four is targeted to low-income families specifically. Because families don’t have to reach an income minimum, a low-income refundable young child CTC, this benefits families in poverty and deep poverty—communities who are unable to benefit from the federal CTC. On the other hand, low-income families are not the only families who could benefit from tax relief. Option Five expands the young child option to middle-class families.

OPTION 4: LOW-INCOME REFUNDABLE YOUNG CHILD CTC

Eligibility: Available to families making less than $30,000 with a child under the age of 6

Rate: Sliding scale up to $600 per family. Families who make under $2,500 earn a full credit.

Est. Impact: 179,920 families

Est. Cost: $69,516,000

OPTION 5: REFUNDABLE YOUNG CHILD CTC

Eligibility: Available to families making less than $100,000 with a child under the age of 6

Rate: Sliding scale up to $225 per family. Families who make under $2,500 earn a full credit.

Est. Impact: 786,872 families

Est. Cost: $93,644,00

THE PROGRESSIVE OPTION

OPTION 6: BRING EVERY QUALIFYING CHILD UP TO FULL $2,000 CREDIT

Eligibility: All families currently not receiving the maximum federal credit value ($2,000 per child) – except for those earning too much to receive the credit

Rate: State-level credit set equal to the difference between the maximum federal credit value ($2,000 per child) and their actual federal CTC

Est. Impact: 1.54 million children

Est. Cost: $900 million/year

This alternative supplements the one-third of children whose families earn too little to qualify for the federal child tax credit. By implementing a refundable state-level CTC specifically for those who aren’t eligible for the federal CTC, Michigan would be able to reduce child poverty statewide by 24% and deep child poverty by 33%.[50] According to The Institute on Taxation and Economic Policy, 1.54 million Michiganders would benefit from this policy proposal, including 33% of children under 17. Because it is aimed at those who earn too little to qualify for the federal CTC, it is no surprise that impact is concentrated amongst the poorest populations.

CONCLUSION

A state-level child tax credit is a realistic and substantive policy option to fight childhood poverty in the state of Michigan because it is uniquely positioned as economically, socially, and politically feasible. Research suggests that implementing a state-level child tax credit would lift many Michiganders out of poverty, increase educational outcomes, improve future financial outcomes, and decrease socioeconomic inequality. These six policy alternatives represent the extreme flexibility the state is able to leverage vis-à-vis eligibility, rate, and structure. Some options clearly come with more significant price tags than others, but higher program costs don’t necessarily correlate with more effective programs. In fact, even “modest boosts in income can have substantial positive effects on children’s long-term outcomes.”[51]

It’s also politically realistic. Similar bills have been proposed on both sides of the aisle in previous years (e.g., HB4183 in 2019 and SB0749 in 2018). While both of these bills proposed child care tax credits, which subsidize the cost of child care, not child tax credits themselves, they do point to a Michigan Legislature looking to provide working families with children relief. Additionally, child tax credits have long experienced broad bipartisan support[52], making them an appealing anti-poverty option for a polarized legislature. Moreover, public opinion suggests that selling Michiganders on the measure is doable. Rarely do political feasibility and program efficacy overlap as much as they do for a state CTC; this is an opportunity that Michigan cannot afford to let pass.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

|

Madeleine March-Meenagh is a Graduate Assistant in Michigan State University’s Master of Public Policy Program and a Graduate Research Fellow in MSU’s Institute for Public Policy and Social Research. The Institute is home for policy education, political leadership and survey research in the university’s College of Social Science. Her policy interests include family and community developmet.

[1] “Innocenti Report Card 14: Children in the Developed World,” Innocenti Report Card 14: Children in the Developed World (UNICEF, 2017), https://www.unicef-irc.org/publications/pdf/RC14_eng.pdf)

[2] “New Census Data Reveals Continued Child Poverty Crisis in America,” Children's Defense Fund, October 10, 2019, https://www.childrensdefense.org/2019/new-census-data-reveals-continued-...)

[3] Ibid.

[4] Ibid.

[5] Ibid.

[6] Charles P Larson, “Poverty during Pregnancy: Its Effects on Child Health Outcomes,” Paediatrics & Child Health 12, no. 8 (2007): pp. 673-677, https://doi.org/10.1093/pch/12.8.673)

[7] Patrice L. Engle and Maureen M. Black, “The Effect of Poverty on Child Development and Educational Outcomes,” Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences 1136, no. 1 (2008): pp. 243-256, https://doi.org/10.1196/annals.1425.023)

[8] “Ending Child Poverty Now - Chapter 1,” Children's Defense Fund, April 29, 2019, https://www.childrensdefense.org/policy/resources/chapter-1/)

[9] Gary W. Evans, “The Environment of Childhood Poverty.,” American Psychologist 59, no. 2 (2004): pp. 77-92, https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066x.59.2.77)

[10] See “Ending Child Poverty Now” supra note 8

[11] Ibid.

[12] Ibid.

[13] Robert P. Jones and Daniel Cox, “Attitudes on Child and Family Wellbeing: National and Southeast/Southwest Perspectives,” PRRI, 2017, https://www.prri.org/research/poll-child-welfare-poverty-race-relations-...

[14] Joshua T. McCabe, The Fiscalization of Social Policy: How Taxpayers Trumped Children in the Fight against Child Poverty (New York, NY: Oxford University Press, 2018))

[15] Ibid.

[16] “What Is the Child Tax Credit?,” Tax Policy Center, 2018, https://www.taxpolicycenter.org/briefing-book/what-child-tax-credit)

[17] Marr, Chuck, et al. “EITC and Child Tax Credit Promote Work, Reduce Poverty, and Support Children’s Development, Research Finds.” Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, Oct. 2015.

[18] Maag, Elaine and Julia B. Isaacs, “Analysis of a Young Child Tax Credit,” Sept. 2017, https://www.urban.org/sites/default/files/publication/93206/analysis_of_....

[19] Ibid.

[20] Ibid.

[21] Milligan, Kevin, and Mark Stabile. 2011. "Do Child Tax Benefits Affect the Well-Being of Children? Evidence from Canadian Child Benefit Expansions." American Economic Journal: Economic Policy, 3 (3): 175-205.

[22] Marr, Chuck, et al. “EITC and Child Tax Credit Promote Work, Reduce Poverty, and Support Children’s Development, Research Finds.” Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, Oct. 2015.

[23] Ibid.

[24] See “The Fiscalization of Social Policy” supra note 14

[25] Institute on Taxation and Economic Policy and Center on Poverty & Social Policy at Columbia University, “The Case for Extending State-Level Child Tax Credits to Those Left Out: A 50-State Analysis.” Apr. 2019.

[26] Marr, Chuck, Chloe Cho and Arloc Sherman. “A Top Priority to Address Poverty: Strengthening the Child Tax Credit for Very Poor Young Children,” August 2016, https://www.cbpp.org/research/federal-tax/a-top-priority-to-address-poverty-strengthening-the-child-tax-credit-for-very

[27] “Working Family Tax Credits,” Idaho Center for Fiscal Policy, Feb. 2018, http://idahocfp.org/new/wp-content/uploads/2018/02/ICFP-Working-Family-Tax-Credits-2-16-18-FINAL.pdf

[28] “A More Responsible Tax Policy for Idaho’s Future,” Idaho Center for Fiscal Policy, April 2019, http://idahocfp.org/new/wp-content/uploads/2019/05/More-Responsible-Tax-Policy-Report-2019-5-16.pdf.

[29] Auxier, Richard and Elaine Maag. “Addressing the Family-Sized Hole Federal Tax Reform Left for States,” Urban Institute, Nov. 2018, https://www.taxpolicycenter.org/sites/default/files/publication/156164/addressing_the_family-sized_hole.pdf.

[30] “Child Care/Child Tax Credit,” Oklahoma Policy Institute, July 2019, https://okpolicy.org/child-taxchild-care-tax-credit/.

[31] Montiel, Jason and Davi Milam. “CA Earned Income Tax Credit and Young Child Tax Credit: Expanding Help for Working Families,” State of California Franchise Tax Board, Sept. 2019, https://www.ftb.ca.gov/about-ftb/meetings/board-meetings/2019/september-12/ca-earned-income-tax-credit-and-young-child-tax-credit.pdf

[32] “The CalEITC and Young Child Tax Credit: Smart Investments to Broaden Economic Security for Californians,” California Budget & Policy Center, Oct. 2019. https://calbudgetcenter.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/10/CA_Budget_Center_1055-CalEITC-Chartbook-Update-October-2019.pdf

[33] “Empire State child credit,” New York Department of Taxation and Finance, https://www.tax.ny.gov/pit/credits/empire_state_child_credit.htm.

[34] West, Rachel. “Harnessing State Child Tax Credits Will Dramatically Reduce Child Poverty,” Center for American Progress, April 2019, https://www.americanprogress.org/issues/poverty/reports/2019/04/16/467299/harnessing-state-child-tax-credits-will-dramatically-reduce-child-poverty/.

[35] Ross, Laura Millard, “Michigan continues to rank in bottom half nationally in child well-being,” June 2018, https://mlpp.org/michigan-continues-to-rank-in-bottom-half-nationally-in-child-well-being/.

[36] Haddad, Ken, “Report shows drop in Michigan's child poverty rate, but disparities among racial groups remain,” April 2018, https://www.clickondetroit.com/news/2018/04/18/report-shows-drop-in-michigans-child-poverty-rate-but-disparities-among-racial-groups-remain/.

[37] Guevara Warren, Alicia S. 2019 Kids Count in Michigan Data Book: What It’s Like to Be a Kid in Michigan. Lansing, Michigan: Michigan League for Public Policy.

[38] Ibid.

[39]Ibid.

[40] Ibid.

[41] Ibid.

[42] Ibid.

[43] See “Harnessing State Child Tax Credits Will Dramatically Reduce Child Poverty” supra note 34

[44] See “Addressing the Family-Sized Hole Federal Tax Reform Left for States” supra note 29

[45] See “The CalEITC and Young Child Tax Credit: Smart Investments to Broaden Economic Security for Californians” supra note 32

[46] See “Analysis of a Young Child Tax Credit” supra note 18

[47] See “The Case for Extending State-Level Child Tax Credits to Those Left Out: A 50-State Analysis” supra note 25

[48] See “Harnessing State Child Tax Credits Will Dramatically Reduce Child Poverty” supra note 34

[49] Ibid.

[50] See “The Case for Extending State-Level Child Tax Credits to Those Left Out: A 50-State Analysis” supra note 25

[51] See “Harnessing State Child Tax Credits Will Dramatically Reduce Child Poverty” supra note 34

[52] See “The Fiscalization of Social Policy” supra note 14