Last month, the 116th Congress convened in Washington, D.C., while newly elected officials took office in state and local roles across the country. Rightly so, there has been a lot of focus on the number of women taking office in 2019, with 106 women being elected to the U.S. House of Representatives and 25 to the Senate, both marking record numbers. Record numbers of women are taking office throughout the United States, including in Michigan where Gretchen Whitmer, Dana Nessel, and Jocelyn Benson were elected Governor, Attorney General, and Secretary of State — with a record number of women also elected to the state legislature.

Although it has been given less attention, younger candidates also made significant gains in the 2018 election. According to Pew Research, the median age for incoming Democrats in the U.S. House is 45.8, while the median age for re-elected Democrats is 64.3 years old. For Republicans, the median age for newcomers is 48.9, while the median for those re-elected is 58.4. Millennials make up 6 percent of the 116th Congress, after making up just 1.1 percent of the 115th Congress, and Gen X-ers have increased their representation from 27.1 percent in the 115th Congress to 31.5 percent.

This influx of younger elected officials marks a shift from not that long ago. Do an internet search for “Why aren’t more young people running for office?” and the results are nearly endless. A recent study by Pew Charitable Trusts and the National Conference of State Legislatures put the average age of state lawmakers around the country at 56 years old, nearly a decade older than the average age of the U.S. adult population at the time.

Whether the number of young people elected in 2018 reflects a trend, or a blip on the radar remains to be seen, but comparison between the demographic makeup of our elected officials and the people they represent is not likely a discussion that will be over anytime soon. In considering this, we ask what motivates people to take the step to run for office? What is it that pushes people beyond “I could do a better job than Congress does” to actually take the step of running for office?

To answer these questions, we surveyed candidates for office in Michigan about the motivations for running for office. One hundred and forty-nine candidates for offices ranging from township trustee to U.S. Congress completed our survey in late summer 2018. From this data, we identified four key takeaways that might identify ways to encourage younger candidates to run for office, ensuring that 2018 is the beginning of a trend, and not a blip on the radar.

1. Younger candidates respond more positively to encouragement from friends and family members.

Encouragement from other community members is likely to be an important catalyst for participation in government, making it likely to play a key role to run for the office. The chart below shows responses about who encouraged the candidate to run for office. The question allowed multiple responses. Just under 73 percent of our total sample were encouraged by someone to run for office. The people who encouraged participants to run suggest some interesting differences in candidate recruitment. Most importantly, younger candidates were more likely to cite family members and friends as a primary source of encouragement while older candidates were more likely to be encouraged by someone outside their inner circle.

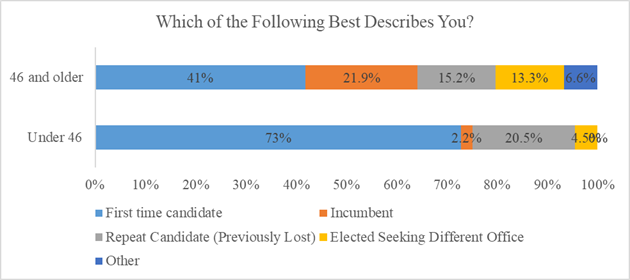

Party officials and elected officials were less likely to encourage younger candidates to run. They are largely encouraged by their relationships with others who are involved with the political process. This is not terribly surprising given what we know about who regularly interacts with public officials. It might also suggest that there is limited engagement between younger generations and government officials. It also may be informative about who is regularly engaging with current elected officials and to whom current elected officials seek to engage. This result is also consistent with younger candidates being more likely to be running for the first time. Since there are many previous election winners in the group 46 years old or older, these candidates are likely to have been able to develop close relationships with officials and community members. On the other hand, 73 percent of those under 46 were first time candidates.

2. Younger candidates feel less qualified for the office they are currently running for, but also feel more confidence about their abilities in general

We also asked these political candidates to assess their knowledge, qualifications, and abilities to succeed in the office for which they are running. We asked them about their confidence level on a scale of one to 10, where one was not at all confidence and 10 was very confident. Older candidates felt more confident in their knowledge of the responsibilities of their office and in their qualification for the office they sought. The difference in how qualified candidates felt was statistically significant.

Based on these seven questions, we created an overall self-assessment score for each participant. According to this composite score, younger participants were significantly more likely to rate themselves as having the skills for public office, despite feeling less qualified.

3. Younger candidates are less trusting of federal and state governments.

It is logical to think that politicians might be hypercritical about an incumbent government, since so many campaigns focus on criticizing current regime as a means of justifying their running for office. The figures below suggest that Michigan primary candidates are perhaps more trusting of government than one might expect. Regardless of age, candidates were more likely to trust local government to do the right thing.This is perhaps not terribly surprising as most participants in this sample already have a close relationship with their local government.

4. Younger, first-time candidates are more likely to have previously considered running for office and more likely to be interested in resources to prepare them for a campaign.

In our sample, 77 percent of first-time candidates under 46 had previously thought about running for office, but had not done so. For those 46 and up that number drops to 26 percent, a statistically significant difference. Among those first-time candidates, younger candidates were also significantly more likely to say that information and training on campaigning would be useful or make them more likely to consider running for office.

This finding is borne out by groups like Run for Something, and their counterpart Republican groups, that encourage and train people to run for office. Though more heavily concentrated among Democrats (14 of the 20 millennial freshmen members of Congress are Democrats) across the spectrum, younger candidates are participating in training programs and connecting with resources aimed at preparing them to run for office.

This preliminary research suggests multiple ways to encourage younger candidates to pursue public office and civic engagement:

Elected officials, party officials, and other involved in candidate recruitment should be more proactive in encouraging younger candidates. There is nothing to suggest younger candidates make for worse elected officials, so why not encourage them to pursue this route of political engagement?

We should talk more about the skills that make for an effective public official. If young people rate their skills highly, yet don’t feel confident that they are qualified for office, perhaps there is a disconnect there that needs to be addressed. This could be an area for further research.

We should continue to support and expand on efforts to educate people about what skills are needed and how to succeed in running for office. The demand is clearly there, and it appears to be leading to a more diverse, more representative sample of political candidates, at least in the short term.

Trey Malone is an assistant professor in MSU's Department of Agricultural, Food and Resource Economics in the College of Agriculture and Natural Resources. Eric Walcott is a state specialist in MSU Extensions Government and Public Policy programs. He assists IPPSR on legislative and legislative staff training programs.