During last year’s state budget negotiations for the 2019-20 fiscal year, Michigan Gov. Gretchen Whitmer and the Republican-dominated Legislature were entrenched in a tense political standoff, debating how the state’s budget should be divvied up between departments. This 2020-21 fiscal year was different. In a showing of bipartisan cooperation, the state Legislature passed two budget bills—one for education and one for all other government spending—largely unopposed.

The bills were then signed into law and took effect with the new fiscal year’s opening on October 1. All this was done against the backdrop of the coronavirus pandemic, which has taken a severe toll on the state’s physical and economic wellbeing. This year’s budget reflects that, telling a tale of coronavirus recovery. Totaling $62.76 billion, the 2020-21 budget makes some cuts but drastically increases health spending and economic stimulus.

Because of the pandemic, Michigan ended the 2019-20 fiscal year with a $2.5 billion deficit. What’s more, in the months since the pandemic began, the state has collected 3% less in tax revenue than it did in that same time period last fiscal year. In this regard, however, Michigan fares better than other states. Across the U.S., state tax revenues face an average deficit of 4.9% and a median of 3.6%, according to the Urban Institute, a Washington, D.C.-based policy think tank.

To address its deficit, the Michigan 2020-21 fiscal year budget makes some $270 million in cuts to account for the shortcoming. Some of these cuts include $13.5 million in aid to local governments; $222.6 million in K-12 school aid; $12.3 million with the closing of the Detroit Reentry Center, which rehabilitates reoffending prisoners and parolees, due to a decline in Michigan’s prison population; and various savings in administrative expenses.

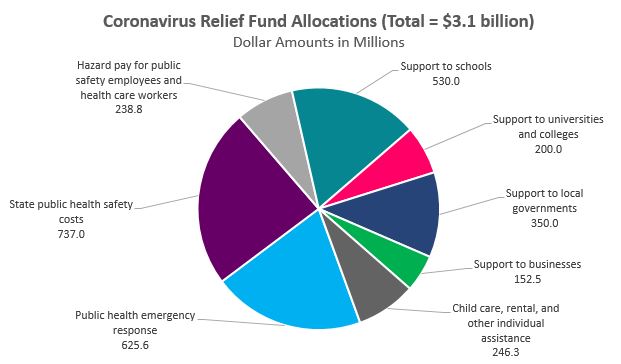

Much of these cuts, however, were offset by funding from the federal government’s Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security Act (CARES), which was passed by Congress to alleviate some of the financial burden incurred by businesses, schools, hospitals, and workers during the pandemic. Michigan earned $3.1 billion in CARES funds and used it to bolster education and local government spending. These funds were also allocated to Medicaid to meet the influx of patients infected with COVID-19.

Source: Michigan Department of Technology, Management, and Budget

In all, accounting for cuts and federal funding, the total 2020-21 fiscal year budget saw a 6.3% increase from the last. This year’s omnibus budget—which covers all state spending except education—comes out to $45.1 billion and the education budget to $17.65 billion. The distribution of funds between agencies shows an attempt to stabilize Michigan’s COVID-infected health and economy. Let’s begin with the gainers:

K-12 EDUCATION: Despite cuts, overall education funding increased, a positive move for students and teachers. For teachers, the state allocated funds to school districts, which will then distribute these funds to individual teachers and administrators. Public or nonprofit private K-12 school teachers will receive up to $500 in one-time hazard pay. A $250 one-time payment will compensate school support staff for pandemic-related overtime. Lastly, first-year teachers who complete the 2020-21 school year will earn a stipend of $500-$1000.

For students, school districts were allocated a one-time payment of $65 per-pupil. An investment of $14.3 million expands internet connectivity for students in low-income communities. $66 million was awarded to school districts with increasing enrollment. Finally, K-12 Special Education received a $70 million boost.

BUSINESSES: To help businesses and community organizations rebound from lost revenue during the pandemic, the government has invested heavily in them this fiscal year. Programs like Business Attraction and Community Revitalization ($20.6 million), community development ($15 million), and enhancement grants (31.2 million)—all of which seek to bolster local economies—earned increased funding. In hopes of boosting the Michigan workforce, $28.6 million was apportioned to the Going Pro program that helps adults earn high school diplomas and gain skill-based training.

Michigan’s tourism industry has stagnated because of the pandemic, stunting revenue for many businesses. As the number of tourists decline, consumer spending decreases, and with it, business revenues and sales tax collections. To counteract this, an extra $25 million was invested in Pure Michigan, the state’s tourism campaign.

To further encourage spending, the government bought $37 million in business tax vouchers and distributed $160 million in federal unemployment insurance.

FAMILIES: An extra $27.6 million was given to The Child Development and Care program, which subsidizes child care to bring costs down for families; this makes more families eligible for its child care services. $23.5 million was added to the Healthy Moms and Healthy Babies program. Now, new mothers and their babies will have health coverage for 12 months instead of the two months provided by previous budgets. A $27.8 million increase will fund youth-related welfare programs like foster care, adoption services, child care, and guardianship.

HEALTHCARE: Because of the coronavirus, hospital admissions have drastically increased, and healthcare spending has skyrocketed. This fiscal year’s budget allocates a total of $28.5 billion to the Department of Health and Human Services, an 8.1% increase from last year. Federal funding, through the CARES Act, covers much of this cost. Medicaid spending increased by $895 million, $796 million of which is federal money. Funding for Michigan’s public healthcare plan, Healthy Michigan, increased by $994 million. Reimbursements by Medicaid to hospital outpatient costs summed $352.6 million. Through a mixture of state and federal funding, direct care healthcare workers will earn a $2/hour wage increase for the next three months.

This budget attempts to rescue Michigan’s economy from the wreckage of the pandemic. Its general trend, therefore, was to increase spending, but not everyone gained. Here are the losers:

FORMERLY INCARCERATED: Not only did the state cut $12.3 million by closing the Detroit Reentry Center, but it also shut down the Lake County Residential Reentry Program (saving $4 million) and ended the Substance Use Services program ($7 million) that provide similar rehabilitation services.

EVERYONE: Despite boosted funding to portions of the state government, no one in this budget can be called a winner. The people of Michigan are in the midst of a pandemic. The state’s economy has been plagued by the coronavirus, and its people are hurting because of it. Businesses have closed and communities have suffered. People have lost jobs, and they’ve lost loved ones. But this budget is the ventilator: it’s keeping the economy alive and preventing it from getting worse. It will stave off an economic recession. It will help businesses, hospitals, communities, workers, and individuals get the resources they need. With it, Michigan can begin to bounce back.

Michael Breslin is an undergraduate policy fellow at IPPSR. He is a junior at MSU studying political science, international development, and history. His primary research interest is economic policy. He previously worked as a communications intern for Mayor Lori Lightfoot of Chicago.