Wolves have received an inordinate amount of attention in the State of Michigan over the past several years. In 2013, Michigan conducted its first wolf hunt, in certain parts of the Upper Peninsula, in response to claims of an overbearing wolf population. In July of 2015, that law was upheld by Michigan’s Court of Claims. Much of the news coverage around the wolf hunting law, and the necessity for it, stemmed from horror stories coming from Upper Peninsula towns, where residents claimed that wolves were entering their yards, and had become a nuisance. However, after the law allowing wolf hunts had passed the Michigan Legislature, a senator apologized for including fabricated stories in a resolution in favor of the law. To add to the confusion regarding Michigan’s wolf population: the State has recently been mourning the fact that only two wolves remain on Isle Royale, the State’s beloved wolf island home.

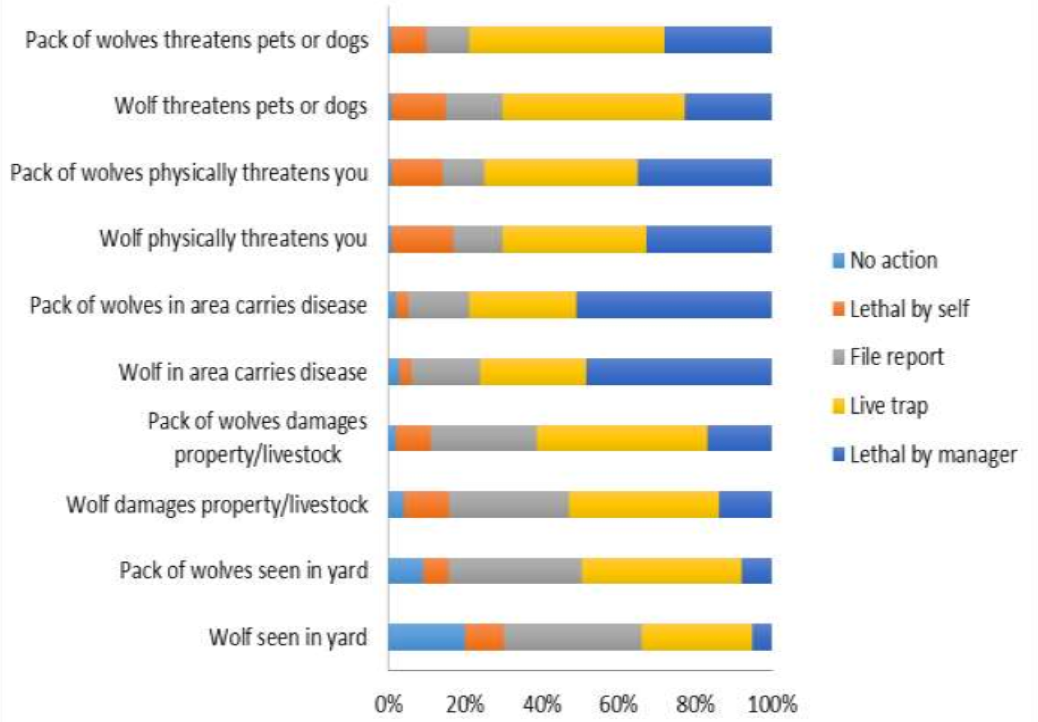

All of these stories beg the question of just how Michigan residents view, and interact with the State’s wolf population. A 2015 Michigan Applied Public Policy Research paper by Meredith Gore, Mark Axelrod, and Michelle Lute attempted to answer this question. They sought to discover how Michigan citizens respond to gray wolves, and the risk associated with them. They conducted a rigorous and comprehensive scientific poll, randomly sampled from Michiganders across the state. One of their main findings: in the graph you can see that Michigan residents are most likely to take no action when they see a wolf in their yard, but are most likely to call authorities to kill the wolf when a pack of wolves in the area carries a disease. The results indicate opportunities for further education about wolf behavior, and current policies. More information, including the paper itself, can be found here.

The paper also examines the multitude of factors that affect how Michigan residents react, and respond to a gray wolf incident. For example, the authors found that the perception of the risk presented by a wolf varied by region, varied by whether it was a single wolf involved, or if there were multiple wolves, and varied by the potential damage that a wolf, or wolf population could inflict in the future via disease. All of these factors play into the equation regarding the State of Michigan’s wolf population, but underlying these factors is the fact that a majority of respondents expressed the desire for the State’s wolf population to remain stable in the future. Further, a majority of respondents expressed the desire that state management agencies, informed by the scientific community should be solely responsible for wolf management in the State. While a plurality of respondents indicated they opposed management decisions being made by the State Legislature.

The paper also examines the multitude of factors that affect how Michigan residents react, and respond to a gray wolf incident. For example, the authors found that the perception of the risk presented by a wolf varied by region, varied by whether it was a single wolf involved, or if there were multiple wolves, and varied by the potential damage that a wolf, or wolf population could inflict in the future via disease. All of these factors play into the equation regarding the State of Michigan’s wolf population, but underlying these factors is the fact that a majority of respondents expressed the desire for the State’s wolf population to remain stable in the future. Further, a majority of respondents expressed the desire that state management agencies, informed by the scientific community should be solely responsible for wolf management in the State. While a plurality of respondents indicated they opposed management decisions being made by the State Legislature.

The bottom line: Michigan residents appreciate their State’s wolf population. They also wish for the State Legislature to stay out of the decision making process regarding wolves’ futures. Finally, the authors go into detail about what these survey responses mean for the potential of educating the State of Michigan about the potential risks of wolves, and the necessity for future education. Interested in the State’s wolf population? Read the report.