This upcoming January, the House Fiscal Agency (HFA), Senate Fiscal Agency (SFA), and Department of Treasury will convene for their bi-annual Consensus Revenue Estimating Conference. Here, the three agencies will compare their individual revenue forecasts and come to a consensus about how much tax revenue the state of Michigan can expect to collect in the upcoming fiscal years. The same thing will happen in May. Each agency drafts its own revenue forecast, then they come together to reach a single consensus projecting Michigan’s tax revenue.

The 2021 conference dates haven’t yet been set, but January’s will likely take place as early as mid-month.

Together, these forecasts are based on a variety of national and state-level economic factors such as GDP, unemployment, home sales, car sales, and manufacturing rates.

The January and May consensus revenue estimates become the blueprint on which the Michigan government bases its budget—that is, how much the state can spend during its October 1 to September 30 fiscal year.

If the three agencies overestimate revenue, the state will spend money it doesn’t have, incurring a notable deficit. If revenue is underestimated, money that would have otherwise been apportioned to deserving departments and programs will be left unallocated. Thus, the three agencies strive to predict tax revenue as accurately as possible.

It is impossible, though, to perfectly predict the future. As anyone could guess, due to the COVID-19 pandemic, the consensus estimates for the 2019-20 fiscal year tragically missed the mark. Because unemployment shot up and consumer spending shot down, the state collected far less tax revenue than expected and ended the fiscal year with a $2.5 billion deficit.

However, this miscalculation is a rarity not the rule. In 2016, IPPSR published an article that examined the accuracy of Michigan’s revenue forecasts for fiscal years 2004-05 to 2014-15. It found that, on the whole, the state’s estimates fairly accurately resembled real revenue. In addition, May estimates were far more accurate than January’s; School Aid Fund (SAF) predictions proved truer than those made for General Fund/General Purpose (GF/GP); and that the House was the most accurate individual agency, but still not as effective a predictor as the overall consensus.

Many of these findings hold true today, with some notable exceptions.

The three agencies, both independently and in consensus, still forecast tax revenue with relative accuracy. In fact, January estimates have improved. Previously, January GF/GP consensus forecasts underestimated actual revenue by an average of $494 million, a 6% difference between projected and real revenue. The average difference now is $414 million, or 4%. Likewise, January SAF accuracy improved from a $175 million underestimation (a 1.6% deviation), to $166.7 million (1.3%)

May forecasts, though, have since declined in accuracy. May GF/GP consensus estimates previously averaged a 3% or $239 million deviation from real revenue. They now average an underestimation of 3.9% or $401 million. SAF has followed suit, worsening from an impressive 0.24% ($26 million) disparity, to 0.93% ($118 million). While not severe, this inaccuracy should raise some eyebrows as the May consensus guides spending in the final draft of the budget.

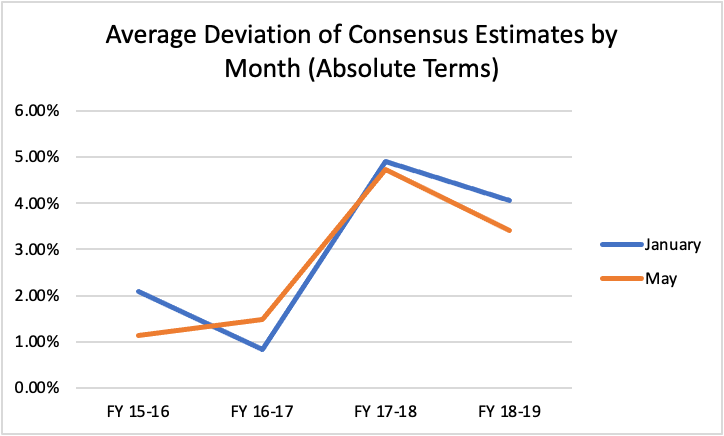

As the graph indicates, with January estimates becoming more accurate and May less, the two now follow a similar trend of miscalculation. In fact, in fiscal year 2016-17, January estimates more accurately predicted revenue than May.

SAF projected revenue remains far more accurate than GF/GP due to a difference in revenue source. SAF derives most of its revenue from sales tax which is less volatile than the income tax GF/GP relies on.

Since the previous article’s publishing, the HFA lost its spot as most accurate revenue predictor—besides the consensus—and has been overtaken by the Treasury Department. That being said, all three agencies have drastically improved their overall accuracy.

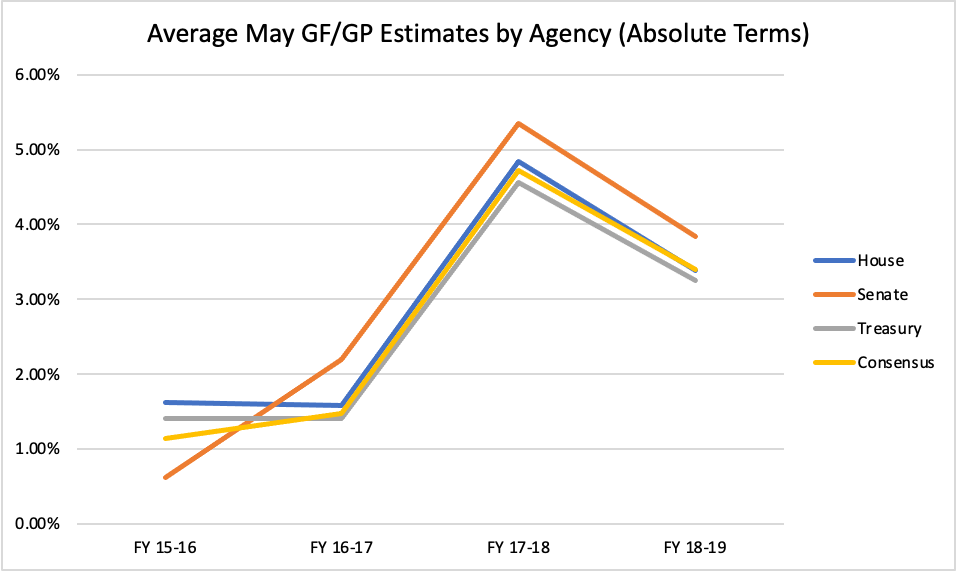

Previously, the HFA’s May GF/GP estimate deviated from real revenue by 3.9%, the Treasury Department by 7.9%, and the SFA, 7.4%. Excluding the HFA, whose May GF/GP accuracy declined to 4.2%, the Treasury jumped to a deviation of 3.4% and the SFA to 4.5%.

An even larger improvement occurred in January GF/GP estimates. The HFA, Treasury Department, and SFA previously overestimated by 12.3%, 13.8%, and 8.4%, respectively. Now, the HFA averages 4.2%; the Treasury, 4%; and the SFA, 3.9%. Accordingly, as evidenced in the graph below, the three agencies, along with the consensus, now follow a very similar path. Impressively, the Treasury Department was even more accurate than the consensus three of the four previous fiscal years, and the Senate beat the consensus in accuracy that remaining fourth year. On the contrary, in the previous article’s analysis, the consensus estimate, without fail, proved most accurate

Just as some estimates improved while others declined, some fiscal year predictions fared more accurate than others. FY 17-18 was the most inaccurate year. Averaging all estimations made by each agency, this fiscal year’s forecasting was off by $585.5 million or 5.2%, in absolute terms. FY 15-16, though, shined as the most accurately forecasted year, with an average absolute deviation from real revenue of only $147.6 million or 1.38%.

Although some estimates have declined in accuracy in recent years—most notably, the May consensus—by and large, forecasting has either improved or, at the very least, held relatively steady. And surely, the individual agencies must be applauded for their astonishing improvement.

As for fiscal year 2020-21, we don’t yet know how much tax revenue the state will bring in nor how closely it will resemble the consensus estimate; we won’t for some time. So, until then, the state and its revenue forecasters must keep on this path, vying for improvement each fiscal year. In the grand scheme of a multi-billion-dollar budget, a miscalculation of a couple million dollars may seem insignificant, yet it could have profound impacts. An underestimation of revenue could leave valuable but underfunded programs reeling for money that the state could have distributed. An overestimation and the ensuing deficit could lead the state to make cuts in the future or begrudgingly dip into its rainy-day fund—a reserve of government money used to stabilize the economy during periods of recession—to restore budgetary balance.

So yes, it is impossible to predict the future, but one must certainly try.

Sources:

Michigan Department of Treasury

Michael Breslin is an undergraduate policy fellow at IPPSR. He is a junior at MSU studying political science, international development, and history. His primary research interest is economic policy. He previously worked as a communications intern for Mayor Lori Lightfoot of Chicago.