The 2016 general election is in full swing. Both presidential nominees are visiting Michigan to lay out their economic plans and attract voter support. According to election forecaster Nate Silver, Michigan currently ranks as the eighth most important swing state (based on the probability that each state will provide the decisive vote in the Electoral College).

Early analysis suggested that Michigan might rise in importance as Donald Trump, compared to prior Republican nominees, was relatively popular among white working class voters and relatively unpopular among minority voters. But the changes in candidate support across states thus far are relatively modest, with Hillary Clinton performing well in all states won by Barack Obama in 2012 and Trump underperforming (thus far) nationwide.

Despite considerable differences between Trump and prior Republican nominees, the geographic and demographic coalitions of the parties appear quite stable. Partisanship is a strong force among voters, making it hard for those who have repeatedly supported one party’s candidate to switch their vote—even with two unpopular presidential nominees.

Both parties also have longstanding advantages among their electorates and swing voters that make relatively close elections the norm. Even with Trump down in the polls, there is no reason to expect a landslide of more than 23 percent in the popular vote—the margin of defeat for both Republican Barry Goldwater in 1964 and Democrat George McGovern in 1972. Both parties easily recovered from those landslides, gaining ground in the next midterm election and winning the presidency in the next cycle.

My new book with David A. Hopkins, Asymmetric Politics: Ideological Republicans and Group Interest Democrats, sheds light on the longstanding advantages of each political party and their bases of mass support. We argue that the Republican Party is the vehicle of an ideological movement that prizes the general principles of limited government, American nationalism, and cultural traditionalism. The Democratic Party is instead a coalition of myriad social groups, each with specific programmatic policy concerns.

My new book with David A. Hopkins, Asymmetric Politics: Ideological Republicans and Group Interest Democrats, sheds light on the longstanding advantages of each political party and their bases of mass support. We argue that the Republican Party is the vehicle of an ideological movement that prizes the general principles of limited government, American nationalism, and cultural traditionalism. The Democratic Party is instead a coalition of myriad social groups, each with specific programmatic policy concerns.

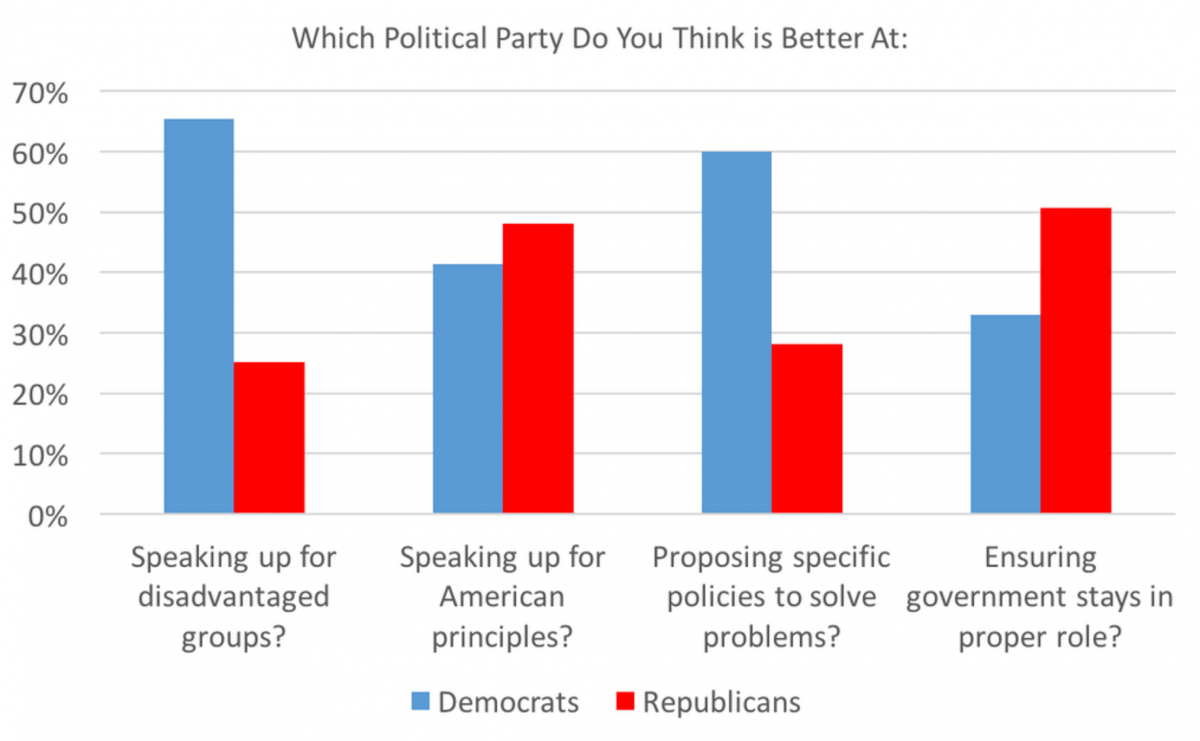

Using IPPSR’s State of the State Survey this Spring, I was able to confirm that Michigan citizens recognize the strengths of each political party. Even in an adult population where Democrats and Democratic-leaning independents represent 52 percent of Michiganders (compared to only 42 percent favoring Republicans), citizens can recognize the strengths and weaknesses of both political parties. Our Democratic-leaning state still gives Republicans credit in some areas.

The graph below shows how the parties’ different advantages reflect the asymmetries in their structure and base of support. We asked citizens to tell us which political party was better at each task, regardless of which one they normally support. Even in an election year, the state collectively gave credit to each party for their different roles. Matching Democrats’ structure as a coalition of social groups with policy concerns, Michiganders give credit to Democrats for speaking up for disadvantaged groups and for proposing specific policies to address social problems. But Republicans also get credit for their ideological stance: citizens favor Republicans for speaking on behalf of American principles and values (by a small margin) and for ensuring government stays within its proper role in our society (by a large margin).

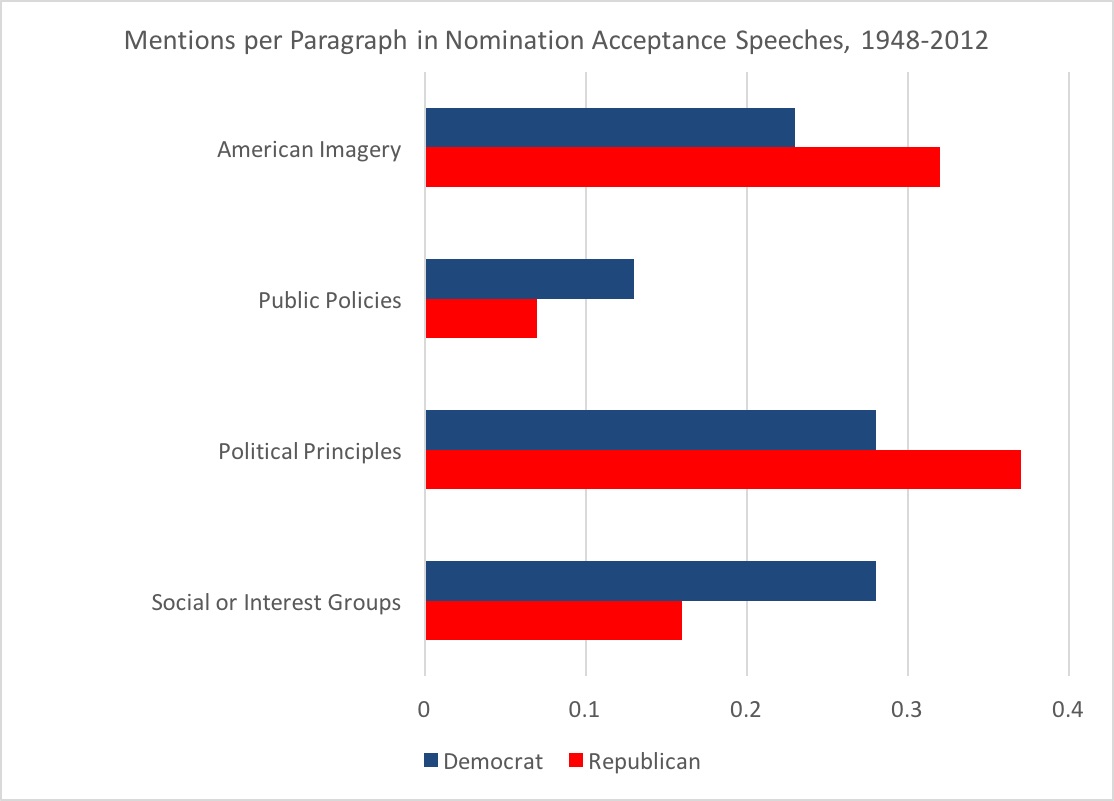

Each party knows its strengths. Republicans consistently emphasize ideological principles whereas Democrats more commonly emphasize social groups and associated policies. Our research, with many examples and datasets, shows that this asymmetry in the party’s presentations is reflected in campaigns, media, research, Congress, and public policy. The graph below provides some evidence from presidential nomination acceptance speeches at the party conventions since 1948. Republican nominees emphasize broad principles and highlight American imagery, whereas Democrats disproportionately discuss social groups and policy proposals.

Even though Donald Trump is a highly-unusual (and inexperienced) nominee, the party’s national conventions in July reflected their strengths. The Democrats did their best to counter their traditional weakness in American imagery, but Trump continued to emphasize threats to the American way of life (the party’s most consistent imagery focus). Republicans put a few minority voices on the stage, but the Democratic Convention featured 11 different interest groups (beyond party or candidate groups) speaking on stage and specific programming dedicated to the representation off 11 different social groups.

Despite a crazy election season, there is no sign that the parties are abandoning their sources of support in the electorate. Michiganders continue to see the strengths of each party, giving candidates a good reason to focus on their parties’ traditional roles.