As an exercise in budget oversight, freshman Michigan legislators recently convened via Zoom to take part in a budget simulation. The simulation was part of IPPSR’s ongoing Legislative Leadership Program offering specialized policy training sessions to new lawmakers.

In this particular simulation, the scenario called for an expected $60 million revenue deficit, and newly elected state representatives were asked to come up with cuts to bring the budget back in balance. That task completed, lawmakers were given an alternate scenario. This one envisioned a $60 million surplus and asked lawmakers to find ways to spend the surplus.

one envisioned a $60 million surplus and asked lawmakers to find ways to spend the surplus.

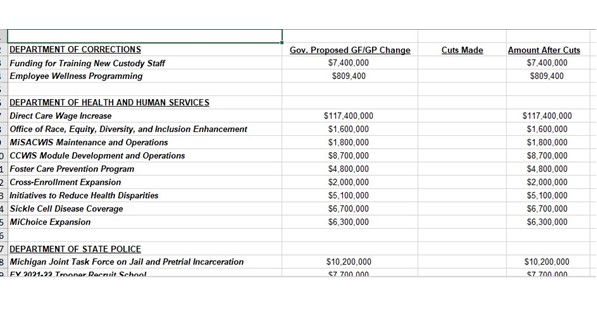

For simplicity, legislators were not given the budget in its entirety. Rather, specific line items from several state departments were used from Gov. Gretchen Whitmer’s preliminary budget recommendation for the 2021-22 fiscal year. A line item is a policy or program allocated funds in a budget. Budgets are formatted as a series of numbered lines; each line corresponds to a given policy and specifies how much money that item will receive. The governor’s budget recommendation is a document outlining suggested changes to those line items for the next fiscal year’s budget.

For example, Whitmer’s FY22 budget recommendation calls for the continuation of a $2 per hour wage increase for direct care workers like home health aides and nursing aides. This line item was included in the FY21 budget and went into effect this last October when the new fiscal year (which runs from October 1 to September 30) began.

When deciding which state departments to use for the simulation, its designers looked for departments with line items heavily funded by General Fund/General Purpose (GF/GP) dollars.

GF/GP are state tax revenues that cover many state expenditures. Unlike restricted revenue, these funds are not earmarked for a specific activity or purpose. Rather, they are allocated in the state budget to any policies or programs agreed upon by the Governor and Legislature during yearly budget negotiations. Put simply, GF/GP are taxpayer dollars that the executive and legislative branches can allocate in the budget however they want, so long as the budget can gain enough support to pass and become law.

And because the Michigan executive and legislative branches are free to allocate GF/GP revenue how they collectively see fit, so too can they cut GF/GP revenue from the budget however they deem necessary. Therefore, the line items chosen for the simulation were largely composed of GF/GP dollars, because in a real-world budget crisis, those are the items from which the government could cut without legal restriction (while still maintaining enough votes for the budget to pass).

In the end, the simulation presented legislators with 20 line items totaling $321 million dollars to cut from (and, if they finished both tasks, to add to). The items are from state departments with large proportions of GF/GP funding: Department of Corrections, Health and Human Services, State Police, Technology, Management, and Budget, and Natural Resources.

Now, it’s pretty easy to put together a simulation from the comfort of my childhood bedroom in the Chicago suburbs, where I’ve been remotely learning since last March. The only decisions I’m tasked with are what line items to include and how best to format a spreadsheet. It’s a lot harder to decide where to cut $60 million from the state budget. So, instead of just telling freshman legislators to make those decisions, I tried it myself.

My key takeaway? Budget cutting is hard! I had to choose between such deserving programs as racial equity training, mental health resources for corrections officers, and foster care expansion. And the fact that I struggled to make these cuts speaks volumes about how difficult it is in the real-world, because I had no one to answer to but my own conscience and ideological leanings.

That being said, I did try to put myself in the shoes of a legislator who must work to compromise with colleagues from the opposite party. I made tradeoffs between what I thought Republican and Democrat legislators would want to cut. For example, I cut equal proportions from a program that would reduce state facilities’ carbon footprint by using more renewable energy and a line item that funds the hiring of new state troopers.

Through all this, I gained a newfound appreciation for the governor and the Michigan Legislature and the difficult financial decisions they are forced to make in times of crisis.

This budget simulation, though, is good practice and preparation for lawmakers for times like Covid-19, when the state had to find not $60 million, but $270 million to cut in state funding from the FY20-21 budget (though most of these cuts were offset by much-debated federal coronavirus relief).

The simulation was a part of IPPSR’s Legislative Leadership Program. The program seeks to inform newly elected legislators on topics relevant to Michigan policy and foster bipartisanship and cooperation. More information on our Legislative Leadership Program can be found here.

The budget line items provided to legislators for the simulation were taken from the House Fiscal Agency’s preliminary review of the governor’s FY21-22 Budget Recommendation. That document can be found in full here.

Finally, a special thank you to Kent Dell, senior House Fiscal Agency analyst, and the entire HFA staff for its help and support on the simulation.

We expect to see IPPSR Undergraduate Policy Fellow Michael Breslin back on campus this coming fall. He’s a junior at MSU studying political science, international development, and history. His primary research interest is economic policy. He previously worked as a communications intern for Mayor Lori Lightfoot of Chicago.